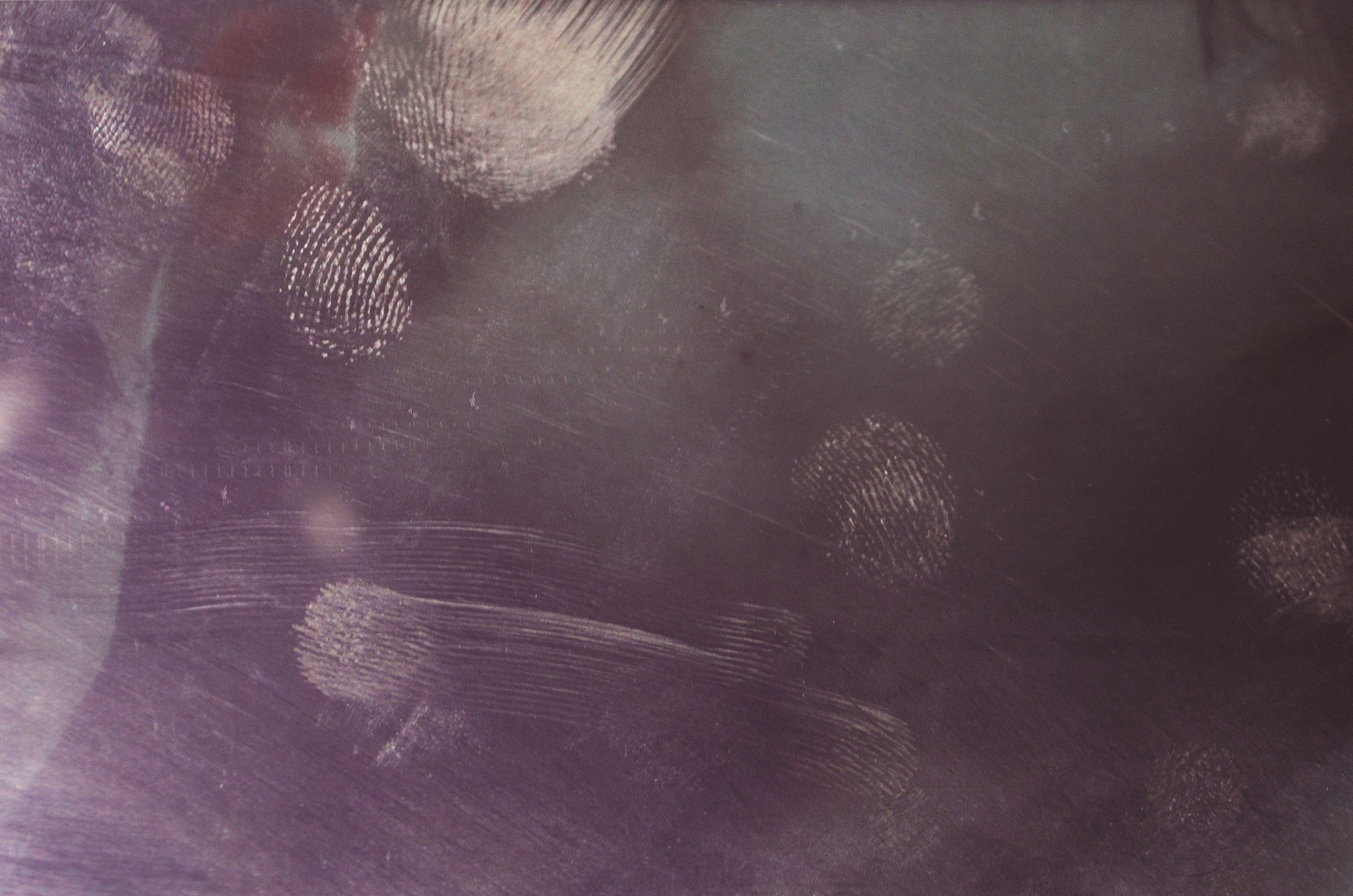

Screen Romance

Photography, 2018-2020

“In Putz’s "Screen Romance", (...) swiping is an expressive gesture. Sometimes it materializes as a decisive, emphatic movement, at other times as an almost tentative touch; sometimes the traces agglomerate into an energetic cluster, at others they remain so subtle that they are barely visible. In their abstraction, the pictures in the series seem like Tachist compositions whose gestural brushstrokes offer reflections of the artist herself. They form a cartography of archival use and bear witness to the intensity with which these images are approached here. We’ve all experienced this. We use our fingers to browse the virtual photo albums of our phones and tablets, at times aimlessly, at times in search of a specific image, which we then unearth like a treasure. Almost every glance is also a touch. We palpate the images, want to know more, zoom into the photo, pause, move the selection, zoom deeper, until the shot dissolves into pores or pixels. Out again, on to the next image, stop, continue, stop, continue, double click, zoom in, and so on. It is a process in which the photographic image comes to life. Digital data may be cold and incorporeal, but photos have always been lifeless matter, dead moments that had to be animated by our gaze and imagination to become carriers of memories.”

- Fabian Knierim, translated by Georg Bauer

Text | Fabian Knierim about Screen Romance︎︎︎

Artist Book PALINOPSIA︎︎︎

“All this talk of analog photography as a reprint, as an immediate imprint of the thing itself, worked as a myth, a narrative of the metempsychosis from the object to its image that facilitated the fetishization of the photograph. And it still works as a fetish, in digital times as it did in analog times: Looking at a photograph allows us to conjure up the past, to visualize a loved one, to bring the old times back to life. And today, like yesterday, a feeling of melancholy remains in light of the fact that we can never fully get a hold of what we yearn for, despite all the presence that photography promises us. What has changed since the days we kept our pictures in shoeboxes are the gestures with which we do the conjuring. If back then it was the careful balancing of delicate prints between our fingertips, now it is a sometimes reckless, sometimes tender brush across a screen. It is precisely these movements with which we animate our memories; they are the traces of an invocation which Michaela Putz visualizes in her work. One might of course ask who exactly we are enticing when we, our heads in the clouds, brush our fingertips across our smartphone’s slick skin. Is our courtship always directed at the great beyond behind the display, or is it the devices themselves, with their hermetic surfaces, their rounded edges, their compact assembly, their inner glow, that awaken in our hands, that are fetish enough to appease our appetite through our mere interaction with them? Sometimes we don’t even have to produce our smartphone from our pocket. Sometimes nothing more than the touch, the familiar weight in our coat pocket, is enough for a reassuring sense of connection with the world and with time itself.”

- Fabian Knierim, translated by Georg Bauer

With the kind support of:

Land Burgenland